First, I want to say a few words about myself and the Intermittent Diet. I wrote this manual to help people understand how they can quickly simplify and, at the same time, maximize their weight loss by using the method of structured intermittent dieting.

My path toward writing Intermittent Diet was different for a diet author. First of all, I’m a guy who studied mathematics and statistics at a university for four years. This was a great time in my intellectual life, during which I realized that math is not just about figures and equations. After training, you develop a mathematical way of seeing the world. There is a moment when math becomes not just your discipline but a way of thinking.

The first time I had any experience in the dieting world was when my girlfriend told me she wanted to try a low-carb diet plan. I wanted to be sure she was trying something safe for her health, so I researched. Before this time, diet talk for me was similar to fashion talk. I had never given any deep thought to dieting.

I started reading popular fitness magazines, blogs, and forums, and after a while, the topic of dieting caught my interest. I continued by studying books on weight loss, nutrition, and biochemistry and consulting several diet experts. Since I was initially trained to work with quantitative data, I also collected data from different experimental weight loss studies to determine what models could fit their findings. My new goal was to determine whether any concepts constantly proved their long-term effectiveness.

The first important information I found was that caloric restriction, even without specific food restrictions, is necessary for effective weight loss. Another interesting finding was the importance of simplicity in the dieting process. A calorie-restricted but complicated diet has been proven to work short-term only. The most astonishing discovery was that, by default, there are two different phases of human metabolism: fed and fasted. The fasted metabolic state promotes a significant fat-burning effect. However, almost 99% of diets don’t advertise this fact.

All these principles apply to the Intermittent Diet, making it the universal solution. Following the Intermittent Diet manual, you can lose weight and prevent weight gain. Or, if you enjoy some diet plan but find it brings you limited results, then the Intermittent Diet is still for you. It can be a great complement to or even a critical missing link in your fat-loss nutrition program.

Big Leap or Small Steps?

I want to begin this manual by presenting a model which shows why it is more feasible to lose weight by dieting intermittently than it is to lose weight with traditional dieting. First, I will uncover the link between weight loss rate and diet to see how it can be applied to diet design. To do that, we need to conduct the following experiment:

Let’s randomly select a considerable group (over 100,000) of overweight and obese adult men and women and instruct them to diet for a week. We will be vague and allow our imaginary participants to choose between many diet plans: low fat, low carb, high protein, vegetarian, or whatever they want.

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll assume their exercise level is light or moderate – since it is not easy to be very active while carrying extra body weight – and we’ll suppose no person in the study is fasting more than two days per week.

Our imaginary experiment aims to examine the most likely rates of weight loss per week in the human population from dieting and to determine how often each outcome may happen. You may expect a broad range of results since many people follow different diet regimes. After all, each person is unique in their characteristics and lifestyle.

Our results will be narrow if we consider that body weight (like height, life span, bone density, etc.) is a biological variable. And when scientists need to predict the values of physical variables, all they need to know is their average value. Then, they get their results by using the law of normal distribution.

The law of normal distribution….sounds like a sophisticated term, but it is pretty easy to understand without mathematical formulas. To illustrate it, I will use human height.

The law says that if one man in six has a height above 177 cm., then we can predict that only one man in 3,500,000 has an elevation above 217 cm., and only one human being out of a billion has a height above 227 cm. The tallest person on the planet is 236 cm tall, so these predictions are very close to reality.

Applying the same law and assuming the average rate of fat loss per week is 1 pound, we will get the results for our experiment. I will skip all technical details and formulas and present the outcomes only.

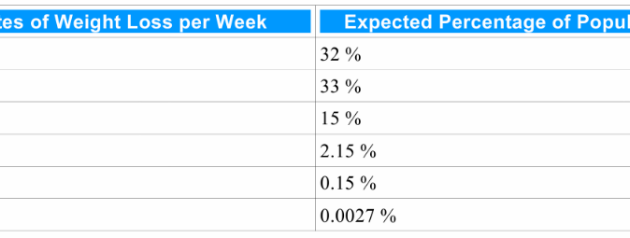

Chances of losing a certain amount of body weight per week under the terms of our experiment:

You can see how irregular weight loss rates are distributed throughout our population. Chances to lose weight within a given range drop off quickly as you get away from the average 1 pound. In our experiment, weight loss chances decrease by about 12,000 (!) times if you want to try to lose 6 pounds a week. What most of our participants should expect from dieting is a weight loss of somewhere between 0 – 3 pounds per week.

Note that weight loss rates slow down as fat mass levels decrease. After losing significant weight during the first months of your body transformation journey, you will not likely continue losing 1-2 pounds a week during the following months. Weight loss may slow to 0.5 or even 0.25 lbs, depending on how much fat is available.

This rate may appear relatively slow to you, but it is pretty acceptable for body transformation since it is obvious you don’t need to lose 1,000 pounds to bring yourself back into shape. Consider also that forcing weight loss to happen faster than it should have some undesirable consequences. You risk developing health disorders like gallstones if you’re trying to lose weight too quickly. Another concern is that losing weight too fast may result not only in fat loss but in muscle loss as well.

It is becoming clear now that losing excess weight in one day is impossible, regardless of how hard you try. Your total weight loss will result from the sum of your collective efforts, not from a single effort or a few efforts. In other words, you are more likely to achieve your goal by taking several small steps rather than trying to commit one big leap.

The same is applied to dieting. One week of dieting does not make your body super lean – just a bit leaner, although months of dieting are more likely to do that. This rule works in both directions. Weight gain doesn’t happen in one day. Overeating in one day adds only a tiny percent to total weight gain.

So, if TOTAL weight loss takes an EXTENDED period to happen, and if a small part of that period contributes only a tiny amount of weight loss, then we can describe the weight loss process with the following line:

The distance between any two dots on the above trend is one week, and since each week is associated with a mild reduction in body weight, the whole movement is also gradually descending.

This trend model helps to explain why even small but long-term changes in eating habits and physical activity, or what people usually refer to as lifestyle changes, eventually outperform radical but short-term solutions and can lead to lasting results.

Considering that weight loss results from calorie restriction, we can build a similar decreasing trend for total calorie deficit during a dieting period. That’s because calorie intake, like the rate of weight loss, is also a non-scalable variable, meaning you can’t eat or burn your monthly norm of calories in just one day.

Under our models, it becomes clear that losing weight doesn’t necessarily require constant dieting. The only thing needed is to be in a calorie deficit throughout some period.

And this is precisely how intermittent fasting works. You will not be in a calorie deficit for most days out of the week, but for one or two days, you will be in an extreme calorie deficit. As a result, over a week, your food intake, on average, will drop, making it possible to lose weight.

It makes a lot of sense. However, part-time dieting must be fully recognized in the fitness world because it involves short-term periods of not eating. This is something we are going to discuss next.

Misconceptions Related to Fasting and Dieting

You’ve often heard or read the claims that not eating enough food will cause you to store more fat. This argument is the so-called “Starvation Mode” theory (a non-scientific term, by the way). According to this theory, two adverse effects are caused by low-calorie dieting:

- 1) Eating too few calories will slow down your metabolism. As a result, you burn fewer calories, and your weight loss decreases to a very minimal rate.

- 2) Your body utilizes muscle for fuel instead of stored fat, decreasing muscle mass.

Based on these two points, some experts recommend avoiding cutting calories too aggressively and advising you to keep eating to increase your metabolism and maintain muscle mass. These are central points in promoting daily, daily-calorie-restricted diets instructing you to reduce only a small part of your daily food intake.

We must have some basic knowledge to detect the natural effect of low-calorie dieting on metabolism and muscle. Metabolism, or, more specifically, metabolic rate, produces a lot of speculation in the weight loss area, so first, let’s visit it.

By definition, the term “metabolic rate” refers to the number of calories you expend over a day at rest, just letting your body perform its functions – the functioning of the vital organs, the heart, lungs, nervous system, kidneys, liver, intestines, muscles, skin, etc. It is the amount of energy you use to stay alive. This is also known as the basal or resting metabolic rate (RMR).

Your lean body mass (LBM) determines your resting metabolic rate. LBM is comprised of everything in your body besides body fat. It includes organs, muscles, bones, skin, blood, and anything else in your body that has mass and is not fat.

The amount of LBM a person carries highly depends on their height. So, ultimately, a metabolic rate is scalable to height because our metabolic organs are also scalable to height.

Put, the taller a person is, the more lean body mass they have, and the higher the RMR will be.

Also, distinguish RMR from another term related to the number of calories a person burns daily, called Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This metric includes RMR plus the cost of movement. TDEE is higher than RMR and depends on not only RMR but also a person’s daily activities.

TDEE will be higher the higher a person’s overall weight since moving a heavier body uses more energy. When a person loses weight and becomes smaller, their TDEE will decrease, and the number of calories burned daily will decrease, assuming activity is equal.

Can you do anything to increase your RMR? If RMR depends on lean body mass, and if LBM includes muscle, then it seems possible to increase RMR by building more muscle. However, your muscle doesn’t contribute much to your metabolic rate. One pound of muscle burns only 5-6 calories daily, not 50, as is commonly believed (the evidence later).

Remember that most calories you burn daily come from resting metabolic rate. It is hard to control your RMR since it largely depends on lean body mass, most of all its elements, and, to a lesser degree, muscles.

Besides RMR, the second major factor that can significantly affect the number of calories burned a day and that you can control is movement – walking, running, working out, etc.

Intermittent Fasting and Metabolism

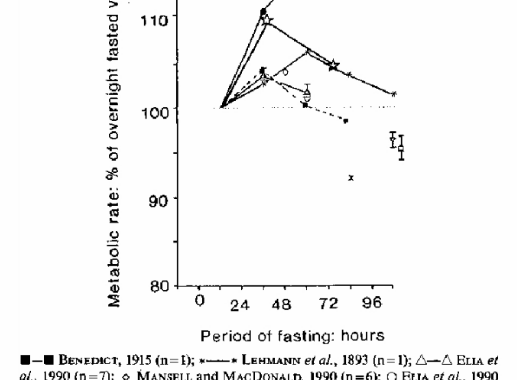

The effect of fasting on RMR is well-known and undoubtedly clear. Research has provided evidence that, during the first three days of fasting, the metabolic rate does not decrease. Interestingly, by the second day of fasting, there is often a tiny INCREASE in resting metabolic rate. Different researchers established this scientific fact over the last century.

But why do we constantly hear that fasting slows down our metabolism? People probably don’t understand the difference between short-term and prolonged fasting and use them as equivalent terms.

So when someone reads a true statement that prolonged fasting causes the metabolic rate to drop, they automatically think that fasting for a day or two also causes this. The resting metabolic rate increases to 6% during the first two days of fasting. Only after the first three days of fasting does it become lower than after an overnight fast.

Changes in resting metabolic rate during early fasting expressed as a percentage of

overnight fasted value (indicated as 100% at 12 hours):

More studies on fasting and metabolism are available in medical literature, and their findings are similar.

In 2000, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition published a study on the effects of short-term fasting on the energy metabolism of 11 subjects. This study was done to keep the subjects under normal living conditions, and its terms are similar to those people face when following an intermittent fasting routine.

The study was performed on an outpatient basis, and the participants were instructed to perform only necessary physical activities (for example, to avoid sports). They were also only allowed to drink fresh or mineral water without added sugar during the study period.

The results showed that resting energy expenditure increased significantly between days 1 and 2 and remained high until the end of the study on the 4th day of fasting. The increase was about 10% higher than the measurement at the beginning of the study.

Frequent meals for weight loss

Another misconception closely tied to metabolism is an eating pattern known as “frequent eating.” This way of eating promises to speed up your metabolism and burn more calories when you eat 5-6 small meals daily. The explanation of why this plan is better for weight loss than less frequent eating patterns comes from a process called “the thermic effect of food” (TEF).

TEF is the number of calories your body burns when processing food for use and storage. A commonly used estimate of TEF is about 10% of total caloric intake4. However, each food component has a specific thermic effect.

For example, you can expect to burn about 40 calories per 1,000 calories of carbs eaten. For fat, the number is 20 calories per 1,000 calories of fat eaten, while protein appears to be the hardest macronutrient to digest – at 100 calories per 1,000 calories of protein consumed.

Does eating six small meals daily help you burn more calories than eating three larger ones? To decide, we need to calculate how many calories will be burned from each eating style, assuming the total number of calories and macronutrients is equal.

Imagine two dieters, both eating 1,800 calories a day. One follows a six-meal routine and eats 300 calories per meal. The other eats only three times a day, consuming 600 calories per meal. Assuming TEF is 10%, we get that the first person will burn 30 calories per meal by TEF:

(1,800 / 6 ) * 10% = 30 cal/meal

For the second person, the number will be 60 calories per meal:

(1,800 / 3 ) * 10% = 60 cal/meal

Computing the total number of calories burned with TEF for the whole day, we find no difference between the two eating patterns. It is the same 180 calories regardless of eating frequency (30*6 = 60 *3 = 180 cal/day).

Of course, you can increase the calories burned from TEF by increasing your food intake. Say, if instead of eating 1,800 calories, you start eating 2,300, your TEF would increase from 180 to 230 since the TEF ratio is always close to 10%.

However, eating more food to burn more calories with TEF is not good weight loss advice because the thermic effect is always lower than the number of calories you eat. From our example, to burn an extra 50 calories, you would need to consume an extra 500 calories.

As the saying goes, it is not worth powder and shot.

Our calculations seem logical, but researching them empirically is a good idea. Here is a scientific study that found no difference between high and low meal frequency:

A study published in the British Journal of Nutrition showed no weight loss difference between dieters who ate their calories in 3 meals daily or six meals daily. All participants had similar calorie restriction diets and lost around 4-7% of body weight. However, there were no differences between the low- and high-frequency meal groups for adiposity indices and appetite measurements before or after the intervention5.

Let’s be more aggressive and further detect the differences between less frequent eating. What eating style has more weight loss advantage – 3 modest meals or one large meal daily?

A study from The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition examined the effects of these two eating patterns on body weight.

The subjects were divided into two groups and put through two 8-week diet periods. During one period, they ate three meals a day, and for the other period, participants fasted for 20 hours and got to eat all their daily food between 5 p.m. and 9 p.m.

Both diets consisted of the same amount of calories in quantities large enough to maintain their body weight, so subjects were not dieting. The results were interesting. Subjects’ body fat was lowered by an average of 5 pounds after consumption of the one meal-a-day diet, while there were no changes in body composition after the three meals-a-day diet.

Researchers described a decrease in body fat by a slight deficit of 65 calories in the one-meal-a-day dieters. If people eat all their food in one large meal, they eat less than three meals.

The bottom line is that frequent meals provide less weight loss than infrequent ones. If you enjoy eating six small meals daily, there is nothing wrong with it. If not, switch to an eating pattern you are more comfortable with. The number of calories consumed matters more than the frequency of meals.

Calorie Restriction and Muscles

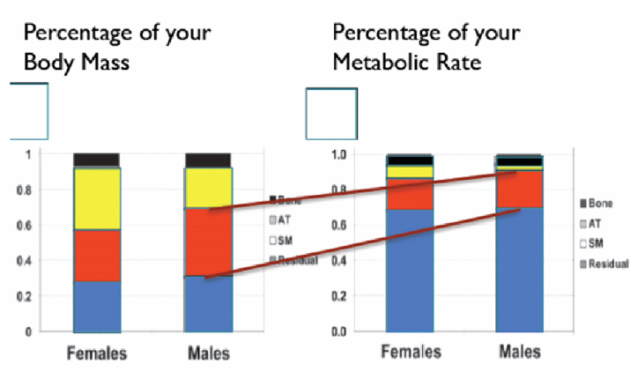

Muscles represent a large part of lean body mass. They create the shape of a body, and adding up muscle mass makes us look fit and younger. Muscle burns calories, though the energy your muscles need daily is usually overestimated.

The simple fact is that one pound of muscle burns 5-6 calories over 24 hours at REST, not 50 like you may have read in fitness media, and not even 10-12 as is stated by people who use the Katch-McArdle formula.

According to that formula, a person’s daily metabolic rate can be calculated as 370 + (21.6 X LBM(kg)). But if you try to use this formula for estimating the increase in your metabolism following an increase in your muscle mass, you will get two times more than you actually should.

That’s because this calculation makes equal the metabolic contribution of muscle and every other component of LBM. In reality, lean body mass is different from a pound of muscle. Parts of LBM, such as the heart, liver, and kidneys, are much more active and burn more calories than muscles at rest.

Even though muscle mass accounts for 40% of body mass, it accounts for only 20% of resting metabolic rate.

The black is bone, the yellow is body fat; the red is muscle, and the blue is the rest of your lean mass…organs, etc.

How does calorie restriction influence muscle mass?

The answer is not as simple as “dieting causes you to lose muscle,” as you may have read. The more accurate answer is, “It depends.”

While we know that PROLONGED calorie restriction can cause muscle loss, nutrition is not a single factor. Exercise plays a vital role in regulating your muscle mass. Exercise can help preserve muscle loss even during long-term dieting.

Research has shown that it is possible to eat very few calories for extended periods with no decrease in muscle mass – as long as a resistance training routine is maintained.

In 2008, a study published in the Journal of Obesity examined the effects of 25-pound weight losses by 94 women. These women followed 800-calorie-per-day diets for up to five months. A portion of the women followed a resistance training workout program, another portion followed an aerobic training program, and a third portion did not exercise at all.

The researchers found that the women who were following the resistance training workout program maintained their fat-free mass during the time they were on a diet. This means they could preserve their muscle mass despite losing 25 pounds. Therefore, all 25 pounds that these women lost were fat.

They also found that the women following the resistance training workout program preserved their metabolic rate. They did not see any metabolic “slow down” due to losing 25 pounds or being on an 800-calorie-per-day diet for five months. On the contrary, both the women who performed aerobic training and those who did not exercise during their 800-calorie diet lost muscle mass8.

Resistance training to retain muscle mass while dieting is tied to the specific structure of muscle cells. Muscle cells are “contractile units” – not “storage units,” like fat cells. While fat cells store or release energy in response to what you eat, muscles respond to work.

If your muscles aren’t used, their size will not increase. Their size will decrease if they aren’t used for a prolonged period. Think of a person wearing a cast, for instance, on his arm due to injury. When the cast comes off, the injured arm is skinnier than it had been or skinnier than a healthy arm. The arm in the cast received the same calories and nutrition as the healthy one. The only difference is that that arm wasn’t being used.

Researchers at the University of Nottingham placed casts on the right legs of 22 individuals for two weeks. The individuals maintained their usual diets, but when the casts were removed, the cross-sectional area of their thighs decreased by 10 percent. All muscle fiber types experienced a decrease in muscle diameter.

Muscle mass will be recovered if you continue to exercise and meet a caloric minimum. Studies found that as few as 80 grams of protein and 800 Kcals per day over several weeks could be consumed while maintaining muscle mass.

Who has a higher risk of losing muscles from dieting – a person with high or low body fat levels?

An extreme military study by Karl Friedl showed that people with low body fat levels have a higher risk of losing muscles from dieting. This study aimed to get the soldiers to lose power, and Friedl found that that happened only when soldiers dropped their body fat levels to 4-6% AND continued being in an average deficit of 1,200 calories per day. One more interesting finding was that once the soldiers reached the 5%-6% range of body fat, they could not lose more.

This could be because individuals with higher body fat levels can oxidize (burn) more body fat per minute. However, as long as your body fat storage decreases, the rate of fat oxidation decreases, and the amount of fat you can lose in a given period is also reduced. People usually call this a weight plateau when they slowly lose those “last 10 pounds” of body fat.

As a final point, remember that building muscle for just burning more calories may not work since one pound of muscle burns close to 5-6 calories at rest. Even if you add up to 40 pounds of muscle mass, you will burn only 200-240 calories daily. That is fewer calories than are contained in a Mars bar.

If you follow a strength training workout, reducing calories doesn’t necessarily cause muscle loss. So, incorporating workouts in your weight loss plan will ensure that all the weight you lose comes from body fat.

Also, I do not advise that you start exercising at the beginning of your weight loss journey, especially if you have high body fat. As you lose weight, you will find it much easier to exercise and increase your activity in general.

The theory

The technique of the Intermittent Diet is based on the idea of “intermittent fasting,” or what I prefer to call “unsteady nutrition.” This term describes occasional breaks from eating, which, in the context of the Intermittent diet, are longer than typical interruptions between daily meals. A similar eating model was inherent to people in ancient times when food intake couldn’t be planned. It was a “eat food when it is available, not when you want to eat” nutritional reality.

Energy obtained from food is one of the elements that the human organism needs daily to live and grow, so adaptation to an environment with irregular food access was vital for the survival of our ancestors. We wouldn’t be alive today if their bodies did not develop this survival mechanism when the next meal time was uncertain.

Fortunately, Mother Nature designed the human body to store excess calories when we eat in surplus and expend them from our energy storage (primarily fat) when we eat less or nothing.

Scientists know that the human body is a complex biological system. And all complex systems, biological or otherwise, survive due to their ability to store surplus. In other words, fat storage is designed to be a form of insurance against volatility in nutrition.

Modern people are lucky now to have stability in their nutrition. However, our genes still think we live in the Stone Age and continue to transform excessive food into energy storage, almost without any limits, creating a big imbalance in the calorie storage/expenditure game.

Despite this, regular meals achieve a level of nutritional dogma nowadays. Some people firmly believe skipping even one meal can make you feel lethargic or weak or slow your metabolism.

A great body of scientific research shows that short-term fasting is influential in establishing a foundation for health. Temporary abstinence from food can be compared to an environmental stressor that stimulates your body and may create a helpful response.

You can make the analogy with resistance training, when we stress our muscles to make them grow, combining short workouts (an hour or two) with longer (a few days) periods of rest and recovery.

Something similar occurs with intermittent fasting; however, here, we usually combine a short-term (24-hour) period of not eating with a more extended (6-day) period of eating. And in both cases, our bodies benefit from these periodic but intense short-term stressors. Remember that some forms of intermittent fasting may involve more frequent fasts; for example, Leangains is a combined 16 hours of fasting and 8 hours of eating.

The benefits

The first benefit of fasting is weight loss, of course. Fasting affects body composition and causes you to lose weight in several ways. As we know, the most fundamental rule of dieting states that energy deficit leads to weight loss. More specifically, every weight loss diet to work should be based on the first law of thermodynamics:

Net Energy Stored = Energy Intake – Energy Expended

If an individual consumes fewer calories than he expends for a certain period (e.g., a week), he can expect to lose weight. On the other hand, if a NEGATIVE net energy balance isn’t achieved for that week, you will hardly see any decrease in body weight. This evidence has been compiled over the past 70 years and is nearly irrefutable. A person who practices intermittent fasting also consumes fewer calories in any given period. For instance, if you take one or two 24-hour fasts in a week, you can expect to eat around 14 or 28% calories less, respectively, for that week.

In this situation, the body must find a way to compensate for that deficit of calories, which it needs to continue to perform all its functions. And the single way to do that is to switch to burning its inner energy reserves. Once external energy sources (food intake) drop to zero level and products of digestion are absorbed, the body starts to utilize body fat actively. This is accomplished by increasing the release of free fatty acids from fat storage, which then are burned by your organs and muscles.

Back in 1993, a researcher named Klein showed that during 24-hour fasting, the rates of fat released for burning increased to 50-80% while insulin levels fell to 35%. The reduction of insulin is necessary for weight loss since insulin is the primary hormone responsible for storing nutrients. When you eat, insulin levels increase, and storage of fat and carbs increases as well.

On the contrary, insulin levels decrease when you do not eat, and another hormone called Glucagon increases. It is a critical hormone that promotes the breakdown of fat cells, while insulin inhibits this breakdown and thus reduces fat burning.

But low insulin is not the only reason body fat is burned during periods of fasting. Scientific research shows that little fat is burned when insulin levels are low IF growth hormone levels are also low. This is where fasting offers a unique fat-burning advantage over traditional diets and any other nutritional plan – fasting reduces insulin levels. It increases levels of Growth Hormone at the same time.

Scientists at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute found that fasting for 24 hours regularly dramatically boosts Growth Hormone to an average of 1,300 percent in women and nearly 2,000 percent in men.

Growth Hormone plays a vital role during fasting due to its ability to regulate metabolism and maintain muscle mass.

When an individual fasts, their growth hormone activates an enzyme called hormone-sensitive lipase, or HSL, which regulates the release of fatty acids from fat storage. On the contrary, HSL is inactive in the body’s fed state, preventing fat mobilization10.

Growth Hormone also helps to protect lean muscle. During fasting, it predominantly stimulates the release and oxidation (burning) of free fatty acids, which leads to decreased glucose and protein oxidation and preservation of lean body mass and glycogen stores.

There are many other health benefits to fasting. During various studies, scientists found that fasting has a broad range of therapeutic effects and can be a tremendous disease-preventing tool.

For one, fasting dramatically reduces pressure on our heart arteries. The more pressure on these arteries, the bigger the chances of a stroke. The amount of blood the heart pumps during fast drops dramatically, giving your heart a rest and increasing comfort.

Fasting also decreases the chances of cancer and can reduce cancer cells in the body. The reason for this is that cancer cells thrive on sugar. When fasting, there is no sugar consumed. Therefore, these cancerous cells slowly die.

Your body will develop excellent immunity to infections and diseases when fasting regularly. You will notice that you don’t get cold very often anymore.

Digestive disorders can be healed with the use of fasting. The digestive system is getting a rest. Our stomachs work 24/7, so keeping them from giving them any work for some time is very important.

And your general feeling of well-being is significantly increased. Fasting as part of your diet will help you feel less tired during the day.

For a diabetic, fasting can lower blood glucose, helping you control your insulin intake.

Blood cholesterol drops when fasting regularly. High cholesterol levels in the blood are responsible for strokes and other heart-related diseases. Several studies have been conducted to prove the positive effects of fasting on health and longevity. As a calorie restriction technique, fasting reduces the growth of a hormone called IGF-1, which contributes to aging. This hormone is one of the drivers that keeps our bodies in go-go mode, with cells driven to reproduce. This is fine when growing, but not so good later in

life.

The difference

Have you ever wondered why people follow a diet for a few months, lose some weight, then stop dieting and gain it all back quickly? Statisticians calculated that if the average dieter starts a diet in January, he abandons it on 18 March.

Why is this so? A diet is claimed to be based on science. The service is professional, and every day you’re getting updates on meal plans for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks, depending on the phase of the diet, timing, glycemic index, glycemic load, or even blood type.

Some may say that the reasons for failed diets are subjective, such as unrealistic expectations or lack of willpower. Still, based on available studies, the number one factor is objective and deals with diet adherence.

Diet adherence is the ability of a dieter to stick to a specific diet plan for some time. This means you need to follow precisely all the rules and recommendations given in a diet.

Each diet contains a different number of rules, and studies have found that a diet plan with a more significant number of regulations has less chance of succeeding, especially in the long term.

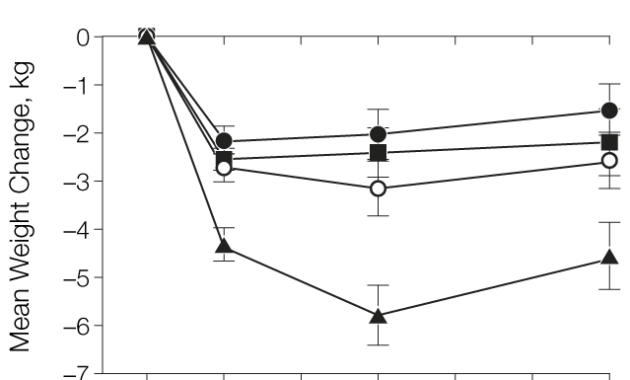

One piece of research that examined the importance of diet adherence for long-term weight loss success is the A-Z weight loss study published in 2007.

In this trial, 311 overweight women were divided into four groups and were instructed to follow one of the following diet programs: The Atkins Diet, the Ornish Diet, the LEARN Diet, or the Zone Diet.

Before the study began, each woman properly learned the details of the diet she was randomly selected to follow. First, she was given a copy of a book about her diet plan to study it herself. After reading the book, she met with a registered dietitian in a class once a week for eight weeks to make sure she knew all the rules of her diet and exactly how to follow them.

When the classes were finished, the women were asked to follow their selected weight-loss programs for one year. The results of the study could have been more impressive. Most weight loss happens in the first two months of dieting. Then, the weight loss tended to slow down or even creep back up.

By the end of the study, no one in any group had lost more than 10 pounds. The Atkins diet was superior to others, although 10 pounds of weight loss could be a better reward for 12 months of dieting. No wonder dieting started getting a bad reputation after the study results were released. The fact that diets work well only in the initial stage rapidly led individuals in the fitness world to believe that diets do not work for weight loss or that they at least work only for a short period.

Later, the findings of the A-Z trial were analyzed by another group of researchers. They were interested in learning whether there was a link between the level of compliance and weight change.

Surprisingly, the scientists found that only ONE woman in the trial had followed her diet as prescribed for one year, while all the others needed help to follow their diets properly and, to some extent, diverged from diet rules.

The researchers concluded that, regardless of assigned diet groups, a 12-month weight change was significantly correlated with diet adherence. The better a woman was at following her diet, the more weight she lost.

Now, think about all the complicated diet plans and all the people trying to follow their numerous rules. Specific macronutrient restrictions, measuring the 30/30/40 ratio, and eating every three hours add nothing but confusion to a dieting process. It is easy to figure out why people eventually give up on such diets – they can’t fit them into their lives.

Despite this, sophisticated diet programs dominate the weight loss market. In his ebook “Venus Factor”, personal trainer John Barban explains that the industry wants to appear to control your weight loss success because this is how they benefit.

For instance, if they make money by selling diet plans, they prefer to offer a complex diet solution to charge you for regular meal updates and ongoing coaching – instead of giving you a once-and-for-all solution. This is a great business model for diet companies but not for their clients, who find it difficult to follow a diet without ongoing assistance.

In general, a complication of a program naturally creates a situation where you need to keep the many parts of your dieting process under control. Of course, you will lose weight, but your results will be fragile. You may easily ruin your weight loss success once you become tired and break diet rules.

The Intermittent Diet is different from the very beginning. It contains a minimum number of rules. You have fewer restrictions, more freedom with your food choices, and flexibility with the timing of your dieting. Here is a table that helps you see the main differences between the Intermittent Diet and traditional (daily calorie-restricted) diets:

The First Phase: Period of Not-Eating

The philosophy behind the Intermittent Diet considers the period of not eating as crucial as the period of eating, looking at dieting more widely than traditional diets. It considers the weight loss process as a whole of two opposite parts and how they need to interact for simple and sustainable fat loss.

Strangely, many dietitians and diet plans have been missing this point for decades, always focusing on the eating part only. During that same time, we began to see a peak in the attitude that dieting is a constant obligation. Like mortgage worries, frequent and obsessive diet prescriptions add a bit of discomfort each day, and they eventually may negatively affect your motivation.

One of the primary nutritional hypotheses is that the human body can be in two opposite states – fed and fasted. Because of these states, the body can regulate and support its energy balance. Adding a time factor, we get two periods into which our nutrition life can be divided – a period of eating (time in the fed state) and a period of not eating (time in the fasted state).

Since you are reading this book, it is likely that, along with many people, you have hardly, if ever, been in the fasted state, so the first action you should take belongs to the 1st part of the system.

Regarding the Intermittent Diet, the 1st part is when a dieter does not eat any food for 24 hours. This time is optimal since it effectively creates a significant energy deficit and is short enough to be convenient and doable for most people.

In addition, 24-hour fasting is harmoniously embedded into our social life cycle. We typically work five days and have two days of rest. This is one cycle, and then it repeats. We schedule most of our usual dealings for a week, and it seems rational to plan and measure our weight loss efforts for a week. A daily focus on weight loss is too zoomed in, and a monthly look is too fuzzy, while viewing your progress weekly will get you a more precise and more correct picture.

How to Schedule Your Fasts

The following plan will help you to simplify things, showing you how to schedule your breaks from eating and counting these 24 hours. Twenty-four hours is an exact number, but be generous. It can be 23 hours or 25 hours. It was chosen not because it is some magic length of time but because it is easy to remember.

There are several possible variations you may experiment with:

1) You can eat as usual until 6 p.m. on day one and then at 6 p.m. the next day. This is an excellent time to take a break from eating if you already follow the “don’t eat after 6 p.m.” rule.

For instance, try to stop eating on Wednesday at 6 p.m. and finish your fast on Thursday at 6 p.m. This means you don’t eat anything right after dinner on Wednesday, have a sleep, then skip breakfast and lunch, and finally eat your dinner on Thursday after 6 p.m.

2) If the first schedule doesn’t fit your lifestyle, experiment with a 2 p.m. to 2 p.m. time frame. The logiс is the same: start a fast after you eat your lunch on day one and expand it until lunch on day two.

3) Do you like or cannot skip breakfast? Then, start your fast right after breakfast. If you have breakfast by 8 a.m., go without food from 8 a.m. until 8 a.m. the following day. Scheduling your breaks from eating this way will make your fasts much easier because you will only go with food the entire day. You will eat every day of the week while being able to do a 24-hour fasting period.

This schedule is a practical application of short-term fasting in the weight loss area. It will help you eat less over a week, improve adherence to the diet in the long run, and free you from fasting for a whole day.

Experiment to find your best fasting day and time frame. In the future, you can easily change your plans if something happens and you cannot fast on your preferred day. It is all up to you.

Tip: Try to stay busy during your fasting period. Fill your mind with positive thoughts and emotions while your stomach is empty. Just forget about food for a time. You will find that it’s much easier to fast when you are busy with work or when you go walking or shopping (last works well for women) rather than being in a passive state. It makes sense to plan your fasts on working days. Moreover, you may become more productive on your fasting days. One obvious thing you may do to increase energy deficit, especially when your body fat level is high, is to switch to 2 fasts per 10 days or two fasts per 1-week regime.

However, remember that too frequent fasts may not fit your lifestyle and may decrease your adherence to the program. It would help if you did some trials to determine what works best for your situation.

Some people make a mistake when they want to speed up the weight loss process or when they need more than one fast a week, and they start to extend their fast from 24 hours to 48 hours or even 72 hours. In this case, they complicate things, forcing themselves to fast and making fasts less flexible so they can easily fit into their lifestyles.

Instead of more prolonged fasts, take the following steps – 1) change your fast time frame; 2) for some time, try two non-consecutive fasts per 10 days or week.

Remember that even though the Intermittent Diet involves periods of fasting, it is not a “lose weight by fasting” method. The program is all about the optimal balance between breaks from eating and rational eating (eating according to your energy needs).

So, keep your fast short-term (24 hours), vary your time frame if after some period you feel you start overeating right after fasting, and temporarily switch to two fasts per 10 days or week regime if your body fat level is still high and if you can easily handle it.

After some practice, you will find the best combination of fasting and eating that helps you lose weight and maintain your new lean body with fewer efforts.

What to Drink While Fasting

Drinking during your fast is a necessary component of the program. It makes your fasts much easier to perform. Drinks also help you avoid a feeling of hunger and maintain a calorie-free intake.

During your fast, you can drink any calorie-free fluids you like. Here is a list of drinks that are OK on your non-eating days:

- Water

- Mineral water

- Sparkling water

- Sugarless black or green tea

- Sugarless black coffee

- Diet sodas

Try to drink more fluids during your fast than usual on eating days. Throughout my fast, I used to drink more than 1.5 liters (2.64 pints) of still mineral water and have two cups of green tea and one cup of black coffee, all sugar-free. Your beverages can be different if your lifestyle and drink choices differ from mine. The idea is to keep calorie intake as low as possible while getting through non-eating days quickly, and this is where drinks, along with busyness, might help.

The Second Phase: Period of Eating

The eating phase is the most straightforward part of the program, and the main rule is the following:

During eating days, you can eat whatever you want, however, not as much as you want. You can eat protein, carbs, and even fat if you keep your calorie intake within your weight loss/maintenance goals.

Learn to eat rationally and enjoy the meals you eat. By definition, all calories are equal, so eating for weight loss doesn’t mean the taboo of some foods and belief in others. After all, dieting while enjoying the food you eat makes you feel satisfied and move quickly through the entire weight loss process.

Here is how to apply this philosophy for your eating days: Examine your diet and create a list of foods that bring you the most satisfaction. There are likely a few things you eat or drink with some regularity so that you may overeat them. So try to eat less of your favorite foods until you reach a point where you can enjoy them but are also eating less of them.

Another step is to create a list of foods and eating habits that won’t make you feel deprived if you exclude them from or minimize them in your diet. For instance, it might be popcorn, which you grab automatically every time you watch TV, but you can enjoy a movie without it. Or maybe you eat a solid breakfast every day just because you have read that it is essential for metabolism, you could quickly eat a small breakfast and be happy.

These changes in eating may appear to be small, but they can significantly impact your weekly calorie intake and make your fasts more productive.

If you already follow some eating patterns and are entirely comfortable with them, you don’t need to break away to switch to the Intermittent Diet style. You don’t need to change anything in your current eating plan. Combining it with the Intermittent Diet’s fasting phase may make a big difference in your results. The best part of Intermittent is that it does not destroy your eating style. It only helps you lose weight more enjoyably and effectively.

How to Track Your Results

Tracking results is a necessary procedure for every diet program. The usual way to measure your progress is by weighing yourself. You may weigh yourself once weekly, on the same day and simultaneously. Only step on the scale sometimes since factors such as body water can make your weight fluctuate by 5-7 pounds within a day.

Besides water retention, there are a few other issues with putting too much emphasis on weighing:

Changes in body weight do not always show changes in body composition. If you lose fat and gain muscle simultaneously, your weight may stay the same on the scales, making you think you’re not progressing. However, if you look at your body circumference, especially your waist measurement, you may notice that it decreased.

Using body weight to guide how much you should eat or move is not a good idea. Weight loss decreases body mass, and as you become smaller, your body starts to burn fewer calories. Over time, your body reaches an energy balance, so to continue losing fat, you must reduce your calories or increase your activity.

If you rely on body weight only, you must figure out this energy balance by counting how many calories you burn. You may load a TDEE calculator online, get an exact number, and then eat several calories below this number. Or you can eat at the TDEE level and increase your activity instead. The concern with this guide is that, in both cases, it involves you in calorie counting.

Since one of the main principles of the Intermittent Diet is simple weight loss, we will mainly use another metric based on body circumference for tracking results during the program.

Waist circumference is an accurate and straightforward way to track body fat levels. It is scalable to height, meaning average waist size can increase/decrease along with an increase/decrease of height within the population. This gives us the possibility to use waist measurement universally for all people.

We only need to calculate a special Waist-to-Height (WTH) ratio. To get this ratio, divide your waist size by height and multiply that number by 100%. For example, for a woman with a 28-inch waist who is 65 inches tall, we get 43% (28/65*100).

Now, here’s how to put all this together with the Intermittent Diet:

=> Above 50%: If your WTH ratio is over 50%, you have excessive body fat, making your body look overweight or obese. So, it’s time for dieting and aggressive dieting.

If you’ve never fasted before, it is recommended that you start with 24 hours once per week for at least three weeks to feel what fasting is like. Also, it would help if you significantly reduce your calorie intake on eating days. Do not go for a certain number; ensure you eat less than before starting the program. As a suggestion, you should cut portions of your high-calorie meals and instead add vegetables and fruits, which are very hard to overeat.

Then, if the ratio is still above 50%, you can increase the frequency of your fasts. You can do 24-hour fasts twice per 10 days, twice weekly, or combine both.

Make sure you can easily handle frequent fasts. There may be periods when you cannot stick with frequent fasts, so you can temporarily switch to fasting slowly and then return to fasting 24 hours once per week.

=> Below 50%: Once you hit the 50% mark, it is time to modify your strategy slightly. You can decrease the frequency of fasts and try using a combination of fasting once and twice per week.

In addition, you should start following some workout routine, which helps you burn extra сalories and, most importantly, maintain lean body mass. Pay attention to how much you eat on your eating days. Again, it has to not work against your fasting and workout efforts. This change aims to bring you to the following WTH ratio range: 47 – 43% for men and 44 – 39% for women.

Once you are in this range, you can decrease the frequency of your fasts and focus on maintaining your new, leaner body. Moving to one fast per week is ideal for this phase. If you eat too few calories on eating days, increase your calorie intake slightly and see how it affects your measurements.

Exercises, especially resistance training, are essential to build muscle and continue shaping your body. For an extra fat loss tool, consider any form of movement you like – running, biking, walking, etc. Physical activity is always easy to perform if it is done with some emotional stimulus. Sports are a perfect example of this.

Generally, it would help if you decreased fasting frequency as your measurements and body fat levels decreased during the Intermittent Diet program. The reverse is also true. If, for some reason, you start gaining fat back, you can increase your fasting frequency in response until you return to your previous level.

Further Reading

If you want more information on intermittent fasting and weight loss, I recommend reading “Eat Stop Eat”, the best-selling intermittent fasting book written by Brad Pilon. You can download the free diet plan from here:

Download the Intermittent Fasting Diet Plan PDF

References

- 1. Garthe I, Raastad T, Refsnes PE, Koivisto A, Sundgot-Borgen J. (2011). Effect of two different weight-loss rates on body composition and strength and power-related performance in elite athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 21, 97-104.

- 2. M. ELIA. Effect of starvation and very low-calorie diets on protein-energy interrelationships in lean and obese subjects. The United Nations University [Online]; Available from:

http://archive.unu.edu/unupress/food2/UID07E/UID07E11.HTM [Accessed 21st December 2012]. - 3. Christian Zauner, Bruno Schneeweiss, Alexander Kranz, Christian Madl, Klaus Ratheiser, Ludwig Kramer, Erich Roth, Barbara Schneider, and Kurt Lenz. Resting energy expenditure in short-term starvation is increased due to increased serum norepinephrine. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000; vol. 71 no. 6 1511-1515.

- 4. Alexandra G. Kazaks, Judith S. Stern. Nutrition and Obesity: Assessment, Management & Prevention. Massachusetts, US: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2012. p. 38.

- 5. Jameason D. Cameron, Marie-Josйe Cyr and Йric Doucet (2010). Increased meal frequency does not promote greater weight loss in subjects prescribed an 8-week equi-energetic energy-restricted diet. British Journal of Nutrition, 103, pp 1098-1101. doi:10.1017/S0007114509992984.

- 6. Kim S State, David J Baer, Karen Spears, David R Paul, G Keith Harris, William V Rumpler, Pilar Strycula, Samer S Najjar, Luigi Ferrucci, Donald K Ingram, Dan L Longo, and Mark P Mattson. A controlled trial of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction in healthy, normal-weight, middle-aged adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007; vol. 85 no. 4 981-

988. - 7. Heymsfield SB, et al. Body size dependence on resting energy expenditure can be attributed to the non-energetic homogeneity of fat-free mass. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism. 282:E132-E138; 2002.

- 8. Hunter GR, Byrne NM, Sirikul B, Fernandez JR, Zuckerman PA, Darnell BE, Gower BA. Resistance training conserves fat-free mass and resting energy expenditure following weight loss. Journal of Obesity. 2008;16(5):1045-51.

- 9. Hespel P. Journal of Physiology (2001), 536.2, pp.625–633; APPELL, H. J. (1990). Sports Medicine 10, 42–58.

- 10. Kenneth B. Storey. Functional Metabolism: Regulation and Adaptation. John Wiley & Sons; 2005. p. 258.

- 11. Miller N, Jшrgensen JO. Effects of growth hormone on human subjects’ glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism. Endocrine Reviews April 1, 2009 vol. 30 no. 2 152-177.

- 12. Mosley M. The power of intermittent fasting. BBC [Online]; Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-19112549 [Accessed 18th August 2012].

- 13. Alhassan S, Kim S, Bersamin A, King AC, Gardner CD. Dietary adherence and weight loss success among overweight women: A TO Z weight loss study results. Nature 2008; 32(6):985-91.